Here are some snippets of a book review I found online:

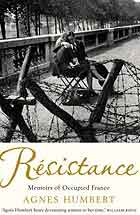

Agnes Humbert is a captured member of the French Resistance and is shipped off to Germany for 'war work'. Immediately after the war, Agnès Humbert, published an account of her four-year incarceration, first in a French prison in the centre of Paris, then as a slave labourer in Germany. Her book, now translated for the first time into English, is unusually detailed, unlike those of many victims who chose not to tell their stories until years later when memory is no longer fresh. Agnes was an unusual woman. Born in 1894, the daughter of an army officer, she became a Symbolist painter and married an Egyptian artist, moving with him to a Breton village to raise their two sons.

She was an early anti-fascist and a woman of the left when those terms meant fellow travelling with the Soviet Union. After her marriage broke up in 1934, she went to work at the anthropological institute, the Musée de l'Homme in Paris, part of a distinguished team of specialists in art and culture that as soon as France fell in 1940 formed one of the earliest organised Resistance groups.

The activities for which she was punished were so paltry: a little newspaper, scrawling slogans on banknotes. But the underground circle was quickly betrayed and its members arrested. A was taken to a prison on the rue du Cherche-Midi, where she spent a year in solitary confinement.

In her coffin-like cell, there is nothing but the loneliness and mental torment of total isolation, apart from a system of communication with the other prisoners whom she never sees. But the French prison is luxury compared with the deportation to Germany. If you ignore, for a moment, Nazi Germany's political ideology and ask what made it tick, the answer is sadism. It enjoyed inflicting pain and reducing human beings to zeroes.

It did not only do this to Jews, Gypsies and Slavs, and its enemies like Humbert, but to its own citizens for pathetically trivial infractions of domestic law. The slave labour units were governed by the same principles as the death camps: work the inmates to death on starvation rations in an experiment to see what the human body can endure before it gives out.

Her account is agony to read and the I am frequently forced to ask if one could have survived more than a few days under the torture she describes. The women are covered in crabs and lice, they are making rayon in factories with toxic chemicals burning their skin, fed on a few hundred calories a day. They have no soap. They own a toothbrush and comb that they continuously steal from one another. Without scissors, their toenails grow into their own flesh. Not even the clothes on their backs are exclusively their own.

What kept Agnès Humbert going was her personality: her will, her optimism and her political beliefs. She is absolutely certain that Germany will be defeated because she believes in a moral universe in which all is set to rights again by human struggle.

But the Nazis are not capable of making her 'destructed'. From the moment she is liberated by the Americans, her formidable powers of organisation are revived, ready to help the newly occupying forces alleviate the suffering of survivors and arrest the perpetrators. She returned to France, but her health was damaged by what she had endured. She died in 1963. Her book adds to the small record of how the human mind can preserve the heart and soul intact against all attempts to annihilate it.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário